An Interview with Mark McCoy

Talking about the past and future of hardcore, the legacy of Charles Bronson, and running an indie label in the modern age.

Hello and welcome to ZERO CRED. In case you missed it, I changed the name of this newsletter last week (from REPLY ALT). Subscribe and get it delivered directly to your inbox.

Mark McCoy and I used to eat BBQ and talk about art for hours. This was back when we were both living in Brooklyn. We’d meet up once a month, gorge on beef brisket, and catch each other up on what we were working on. The main principle I understood, and immensely admired, about his approach to art was that everything should be constantly moving forward. With each new project, McCoy is asking himself what he is adding to a genre or to his own body of work that makes it worthwhile. While many of his hardcore peers are content to coast on the success of a decades-old album or cash in on a reunion tour, McCoy is perfectly happy to create and destroy. He’s launched numerous bands over the last three decades—Failures, Das Oath, and Life Support among them—and most only lasted for an album or two before being shut down. Once he’s said all he has to say, McCoy is onto the next thing. It is a constant reinvention that never settles long enough to gather dust.

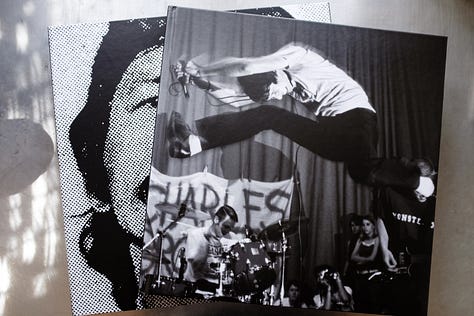

So it was surprising when this notoriously nostalgia-averse artist recently announced that his long defunct cult hardcore band Charles Bronson would be releasing a retrospective box set through his longrunning label Youth Attack. Was McCoy finally softening up and embracing the glory of his teenage years? Hm, probably not. But maybe? After all, his life has changed over the last few years. He relocated to Sedona, Arizona, with his partner, the author and Rose Books founder Chelsea Hodson, who he married in 2021. Yes, the man who wrote the song “Marriage Can Suck It” tied the knot and even welcomed his first child last year.

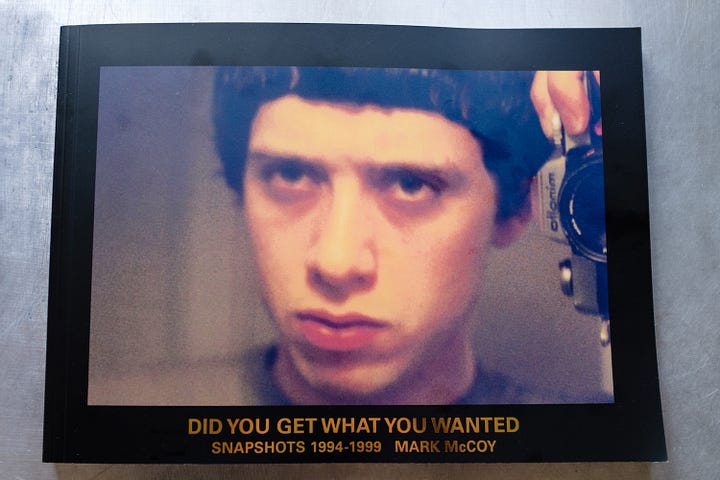

Along with the hefty and absurdly comprehensive Charles Bronson box set (seriously, this thing weighs close to eight pounds), McCoy also released Did You Get What You Wanted, a book of his photos of the Chicago area hardcore scene from 1994 to 1999, featuring Los Crudos, MK Ultra, Spazz, Swing Kids, and dozens more. It also includes a personal essay about the trajectory of the hardcore scene over the decades he’s been involved in it. I recently talked to McCoy about why it was time to briefly take a break from looking forward to look back.

When I was at Noisey, I had a writer do a really great interview with you. And one of the things you talked about was how averse you are to the nostalgia trappings that hardcore bands of the 90s fall into. This new Charles Bronson box set is the closest I’ve ever seen you come to being wistful about the past. How did it come about?

Mark McCoy: In early 2022, I sat back in my chair and realized that the [Youth Attack!] record is going to be 25 years old, and that it was getting to a point where it was irresponsible to not have it available. Because if I continue to ignore it, it would just keep getting bootlegged and they wouldn’t do it the service that I wanted it to have. I had put this off for so long, just because I knew it was a daunting task. And yeah, typically, I don’t look back, because I always have new things that I’m working on, so it’s difficult for me to set that time aside. I knew this was going to be a big deal. It ended up taking two years. It was much more of a big deal than even I anticipated.

What was the biggest hurdle?

The book that came in the box.

What about it?

Every aspect of it, really. What started as a stack of photos turned into me collecting shots from two dozen people and then having my friend in Chicago, Dave Hofer, write liner notes, which typically I don’t like, but he had actually asked me years ago, “If you ever do anything like that, I’m gonna be the one that writes it.” Because he was there for it all. He was like 16 at the time. Even at our last show, he’s the one guy standing on the stage.

He wrote a book about one of the guys in Anthrax, so he is actually a seasoned writer. Then that turned into this huge thing where it was suddenly 12,000 words. He’s interviewing all these people, getting their two cents about the band, and basically chronicling the entire history of the band.

It’s crazy that the history of the band is really just a couple years, and it fills a giant box set like this. Were you aiming to be a completionist?

I started to think of it as a sort of mobile museum, where it contained everything. But the more I got into it, I realized that there was actually a lot of just the last eight months of us as a band, so that’s what the release actually is. So, 1994 to ‘96 is completely left out. So that’s kind of open for debate as to what I do with that later on.

It’s definitely a nerd-type thing, because normally you wouldn’t give a band of our stature this level of consideration. It’s kind of ridiculous, right? But I just thought, “Well, it’s my band and if I’m doing this for history’s sake, I want to have everything in it and for it to be as accurate as it can be.” So that’s where it went.

Has your perspective on any of your life’s accomplishments changed as a result of becoming a father recently?

Well, it is interesting that this [box set] would come out at the same time in my life that I had a baby. It does present this kind of dividing line in my life, where I can look back and think, “Well, this is my greatest achievement when I was young. And now that I’m older, I’ve got this other great achievement.” So yeah, it did kind of seem that way.

But in terms of nostalgia, generally, I’m kind of against it, because I’m resistant to this idea that we can just accept that culture has ended, and I think to a great extent it has. The society we live in has basically killed its culture and all that’s left now is to rummage through the past, and that’s so easily done now. So I wanted to bring this into the present in a way that felt relevant. That’s why I did the photo book with it. The thesis of it isn’t just to collect old pics of these bands, but to present this idea that there was a lot going on and this was all self-motivated stuff that existed on its own. And that has given way, in my view, to this digital ghetto that we live in, where it has forced us into this realm where we have agreed upon this idea of history and what’s acceptable in terms of our creativity, and we just sort of live with it. I wanted to push against that.

I really want to defy the standards of how these things are being treated, because music has become a landfill, to a large degree, and hardcore bands especially are a dime a dozen and they don’t really ever go anywhere. I don’t hold it against the bands, necessarily, because I don’t think they have these kinds of aspirations for the most part. Once they break up, they tend to just be forgotten. And for whatever reason, Charles Bronson has managed to evade that. I think that is largely due to its historical context—when it happened and the way that it played out and how the record has evolved since then. It really is weird. I can’t pinpoint exactly why people still like the band. There’s obviously some factors there that I don’t think you can deny—that it was of the era and it was energetic and it was funny. And I think as a band, we looked really cool. But I don’t know what the average kid these days thinks about this stuff while living in this new digital realm of music and the understanding we have of the past.

You spent two years compiling this book for the box set. Did forcing yourself into that much reflection change your perspective on the band at all? Did you learn anything about Charles Bronson in the process that maybe you didn’t think about before?

Well, it is weird to see photos from shows that you hadn’t seen before. Suddenly you see photos and actually remember some of these people you’d forgotten.

Like the way you would look at a high school yearbook or something.

Yeah. It’s weird to think that these things had just been sitting out there for so long, that people just had them in their homes but they didn’t do anything with them. That’s saying something right there, because they held onto them. They didn’t throw them away. I take that stuff seriously, especially where I’m at now. I make such a point to archive everything, to document. I’m a big journal writer, I keep things. I’m not a big collector. I don’t collect stuff, actually. I am always thinking in terms of posterity, and that is why I kept a journal, even back then, because even though I didn’t have the sense that Charles Bronson would ever be any kind of important band, a lot of info in the book was pulled from my journals—little anecdotes about the shows we played.

What do you think Charles Bronson’s influence was on the scene, either at the time or now?

That’s difficult for me to assess, actually. I think what people were drawn to was the personality, that the band developed a voice that you typically don’t get with hardcore bands. Because it’s very easy to put on the hardcore costume and address the same topics, and you can float by without any sort of consideration. No one’s gonna grill you on your topics. It’s very formulaic in that sense. And I was aware of that, even then, like with Victory Records’ crazy ascent at the time and how boring these bands were by comparison. It became obvious to me that the worse and more accessible you are, the more popular you’re likely to get. Because your crowd is generally undiscerning. They don’t know any better. They’re not the type—generally speaking—that are going to go do the homework and dig through and find these obscure bands, because that’s not what it’s about for them. I think it was more of a social thing, being in the moment, going to shows with friends, and being part of this thing that’s happening. Whereas I kind of looked at it like it already happened, like the best years had already come and gone. We were kind of living in the ruins by that point. Which is funny, because now people cite that era as important.

There’s an element of Charles Bronson that I think is not around today, which is the sort of reactionary humor with which you would poke fun at things. There’s that story in the book about Racetraitor, where you were making fun of them and they couldn’t even believe that someone would poke fun at the things that they were so serious about. I think that’s something that’s been lost. I don’t see anybody taking the piss out of anything anymore.

Well, they won’t let you get away with it now. And the way that it’s structured now is that it doesn’t accommodate that sort of opinion. You will be ruined if you try. You’ll be blacklisted. And I think before anyone even attempts that now, it’s already understood that that would be the punishment. And that is largely why you get what you get. You get a lot of boring bands.

Reading your essay in Did You Get What You Wanted, it’s safe to say you have a pretty jaundiced view of hardcore today. You write that the genre has been dying for years. What would you say to a person who believes hardcore is the most popular that it’s ever been?

Again, this is just my opinion on the matter, but I would say that there’s obviously no classics now. You don’t have the bands that have staying power, and I would say that that’s the evidence right there that it’s collapsed. But again, you get into sort of murky territory because you’re crediting the audience with deciding what is good.

Obviously, I’m a lot older and it’s very typical for older guys to sit and say, “This new stuff sucks! You don’t know what it was like!” I’m very hesitant to be one of those people. I look at it from a perspective of compassion, in a way. Because if you are to actually make this music relevant and endure, you have to diagnose what has made it the way that it is today. And that’s difficult to do because you’re talking about a genre that’s so built upon resistance to everything. The framework of the music itself is so inherently negative that you can’t actually tell someone what to do and have them listen. So you run into all these problems with such a thing.

I look at the American hardcore scene developing out of a very specific time and place in history, but it’s a point in a timeline that is forever ongoing. So you’re wrestling with ever outdated perceptions of what is relevant within the context of the culture. It becomes very difficult to say what it takes to make something vital again. I just think the best thing you can do is to try to be as honest as you can and push what you’re doing in a way that builds upon what has already occurred in the linear fashion. So instead of just being stuck in nostalgia or going for whatever genre you want to be part of, you should actually look at it as the starting point to see where it can go musically, visually, lyrically.

So are you saying that a younger person picking up a guitar today should be studious of the past or that they should completely disregard it and start fresh?

I think you have to know what you’re doing. But it’s interesting, because a lot of my favorite bands, it was like an accident that they were that good. So there’s an element there where you don’t actually need to do the homework if you are divined to be a leader. But those are fewer and farther between now. I don’t really see them. I don’t see these people that have the fire where it’s so obvious that they're a leader.

You write of a younger generation in your essay, “This is not entirely their fault as they are merely the products of an exhausted culture that sold itself out long ago.” That is obviously something I’m very cognizant of because of the book I wrote about selling out, and how this new generation of punk and hardcore bands seems to have no reservations about doing brand deals and even actively celebrate them.

I think it boils down to your perception of the future. Do you think that a viable life awaits you? I think the answer for most people is no. And that’s certainly understandable. So we’re cast into this position now where people really have no choice, in their view, but to just accept whatever crumbs or endorsements come their way in this desperate bid for attention in a world where that attention is always waning. You’re always fading from view. Your possibilities for success are more scant than ever before. And I don’t actually see the music addressing this. It’s kind of like, “We’re willing to play your game. Just give us the beer endorsement or the Taco Bell endorsement and it’ll be funny.” But in the end, you’re just sort of playing into why this problem exists.

It’s really nihilistic. We’ve been raised for a future that doesn’t actually exist.

Well, no one can collectively agree what that future should be. Society is nihilistic. We’ve tacitly agreed that it’s okay that it is. It’s just every man for himself. It’s a feeding frenzy. It really is just kill or be killed. And I think, in the end, everyone just loses, because art suffers. Art is the first thing to go in such a world.

I see this in a lot of guys I know where they’re jovial people one-on-one, but the art they make couldn’t be more bleak and death-obsessed and depressing, because it’s become reflective of their worldview. They just don’t see the chance of any sort of thriving or happiness in the long run. It’s a fact now that most people won’t be able to own homes or have families or do anything normal. And it’s become almost perverse, where you would celebrate the fact that you wouldn’t. That, to me, is the ultimate black pill, where you would celebrate your own destruction. And I understand that listening to music like this is cathartic, but I think maybe it’s reflective of our worst instincts and our worst negative tendencies, because it sort of reaffirms our doubts and our fears, instead of being uplifting.

That’s what I find most perplexing about hardcore today. Yes, the music is reflective of the bleakest times in our history and it’s nihilistic in that sense. But at the same time, to exist as musicians, bands have to play these happy capitalist games, where they’re saying “Thanks, Spotify, for adding us to your hardcore playlist! Thanks, Apple Music.” It’s such a weird dichotomy, you know?

Yeah. Where’s the promotion of more uplifting values? Heroism or truth, you just don’t see it. Everything just feels so corrupted and tired. Name any movement. Straight-edge, for example. It’s just utterly dead. There’s still bands going, doing the thing, carrying the message, but it has been hollowed out. It doesn’t really mean anything anymore. And I think that runs the gamut of the whole landscape that we’re in. Nothing really means anything.

Every generation has had a negative view of effort, where anyone trying to do anything meaningful is looked down upon. That was Gen X’s whole thing, to shit on anyone trying hard. But Gen Z has this added layer of nihilism, where there’s no point to even entertain the idea of trying.

Well, look at their celebrities and heroes. There are influencers or talking heads or celebrities who are essentially famous for nothing. If you can get famous for lip-syncing and get all kinds of product endorsements from it, why would you aspire to do something that would waste so much time and not gain anything from it? Like I said, there’s nothing on the table for these people anymore.

I have always had such a deep admiration for the way you operate Youth Attack, in that you are able to successfully operate a label counter to the way the internet wants artists to work now. Twice a year, you’ll drop everything that you’ve been working on at once. Whereas artists today are encouraged to constantly be churning out cheap, quick hits. Can you talk about your approach to running a label in conjunction with the internet?

Major labels now have flipped and they’re trying desperately to keep up with the audience, and you actually can’t. Because if you let them steer the ship, it’s just gonna be driven straight into the ground. You just can’t allow mob rule. [Laughs] However you define yourself—a curator, an artist, a tastemaker, whatever—you would actually have to go against what is popular and actually risk failure and being ignored. And that’s terrifying to a lot of people. Like I said, money is not really on the table anymore, and people have settled for attention. That really is a telling sign of what people are willing to do and pass off as a creative work. But I really think you must resist that to the best of your ability. I'm not saying don’t ever post anything or don't take selfies.

The way you run Youth Attack, it really is a one-way street. There’s not a dialogue between you and the audience. It’s: “Here are the things that Mark made and you can buy them or not.” And it seems like you have a following that has stayed with you for years.

Oh, decades, actually. There’s people out there that have been buying from me from the beginning, people that are now in their 40s or 50s. So yeah, I feel very fortunate. Obviously, I adore those people. You know who you are. [Laughs]

But I think it just comes down to a quality concern, that you can only put something out when it’s ready. My friend Peter Sotos once told me, “I just hate experiments. I don’t want to hear your stupid experiment. Give me the finished thing.” And he’s absolutely right. You have to just put the work in and make it what it needs to be so that it goes out into the world as a fully realized vision. Don’t give me your little sketch or your little tossed off thing, because it’s apparent. Maybe people don’t care or they’re drawn to amateur aesthetics. I understand that, but I’m past that. I understand the difficulty in making things, so I’m looking to see that reflected in things that I could enjoy. Show me the passion and the pain that went into making this thing. That’s what I’m drawn to, because it’s so easy to just do stuff now, but it’s actually really hard to do a good job.

Back to Charles Bronson, when the box set got announced, I saw some people online surmising that the box set was signaling that there would be a Charles Bronson reunion. Are you still opposed to that idea?

Yeah. I don’t see a reason to do it. I think if someone from that era were in a desperate position, like you’re dying and you need your medical expenses covered, I think that might provide a reason to do so. But even if we did play a show, it would be in a Dekalb basement to 20 people. That’s the only way I could see it happening. No, I don’t want to fly to your stupid-ass fest in Texas and play on this six-foot stage with this big PA system. We won’t sound good, it won’t be good, trust me. We’re all old now. It’s corny. When you see bands doing this, I find it very depressing, because the effort you put into doing this could have gone to something else. It could have gone to something new that’s more relevant. I’m not saying old bands aren’t relevant. And I have seen great reunions. I don’t mean to be totally unilateral about the whole thing. I’m just saying, my preference, as someone that makes things, is always a forward-thinking view, so it would feel very unnatural to go against that and play a show.

And what made Charles Bronson specifically very special was that it was a youth movement. It was a youth attack! It was kids who had this sort of amateur charm and it didn’t last very long. There are some bands that, just on principle, I can’t really see the point in a reunion, Charles Bronson being one. I think Minor Threat, Op Ivy. The youthful magic would be gone.

Absolutely. Those are great examples. Just from my own perspective, it was so youth-focused and so of the time and place that it would feel like I was playing pretend. I would be putting on a costume to do that. I really feel like, as a conceptual idea, the band expressed everything it needed to and ended on a high point and it didn’t need to say anything else. It’s not meant to last. It’s such a passing phase.

I recorded that record with my friends right as I moved out of Illinois to New York. My life changed dramatically after that. Even then, just six months or a year later, it felt so far behind me. But that was by choice. We could have kept the band going long distance but it just didn’t seem sincere. It would no longer be about DeKalb and it would no longer be about the Fireside or our friends. We would be pandering to the attention that we got after the fact. And I didn’t really know that this existed until years after. When I first went to Europe with the Oath, people started coming up to me, asking for my autograph because they knew I was in Charles Bronson. That was pretty shocking—people in Italy or Czech Republic or Germany knowing who I was. I just had never considered that could ever happen.

There’s a store here on Sunset Boulevard that sells bootleg Discharge shirts and those kinds of things. And sure enough, they have the Charles Bronson shirt. What do you make of creating something that hit that level of, not fame, but certainly recognizable cult status?

It’s surreal, because it really has nothing to do with me. It’s this thing that I did so long ago and people like it for whatever reason. But I really have moved on from it, and people may not like the sound of that. But as much reverence as I hold for the band, it’s kind of like it was sent out into the world and it’s no longer mine. I just think the bootlegs are bound to happen. That’s part of the scene, that’s part of the genre, that’s what people do. I guess we’ve tried to combat it to some degree, because people are outrageous with it and I think it’s kind of disrespectful. Because we’re all around. You can certainly contact us. It’s a little rude that they’re trying to make money off us, because we were never about that.

Is it weird being a hot Discogs item band? What do you make of people reselling seven inches for 10, 20 times what you were charging for them originally?

Again, that is the supply and demand issue. With something like Discogs now, you just can’t get around it. The only way to combat that would be to risk putting up all this money to keep the thing forever available to drive down the value so that these flippers can’t profit. It’s a bit absurd.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow me: Instagram | Threads | Bluesky | Twitter | Website

Real life: PO Box 11352, Glendale, CA 91226

Get my book SELLOUT at Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

Mark is friends with Peter Sotos? What the fuck?