Rank Your Records: Metric's Emily Haines and Jimmy Shaw

Canada's beloved indie rock stalwarts play favorites with their deep catalog.

Hello and welcome to REPLY ALT, the greatest newsletter about music in the entire world. Subscribe and get new posts, interviews, and podcast episodes sent right to your inbox. Totally free! If you want to support me further, you can upgrade to a paid subscription for a measly five bucks a month, which also gets you my weekly column about rock books and discounts/early access to all the stuff in my store. In fact, I will knock 50% off subscriptions, here ya go:

In Rank Your Records, I talk to artists who have amassed substantial discographies over the years and ask them to rate their releases in order of personal preference.

When the pandemic began in early 2020, Metric frontperson Emily Haines predicted that she wasn’t going to feel creatively motivated during such a stressful time. She phoned her guitarist and longtime collaborator Jimmy Shaw with a warning: “I was like, ‘This is terrible, and there’s nothing good that’s going to come of this. I’m not going to be writing, so just prepare yourself for that fact.’ And he was like, ‘I’ll talk to you in 48 hours.’”

And sure enough, Shaw was right. Haines and Shaw’s indomitable creative energy thrived even stronger through the pandemic. They holed up in a remote location and wrote so many songs that they wound up with two albums’ worth of material. The first, Formentera, was released in 2022, and now, a year later, they are set to unleash its counterpart, Formentera II. The 18-song, two-part release provides a sense of closure for the unstable pandemic time, Haines says. The albums bookend a difficult era, beginning with the song “Doomscroller” and ending with “Go Ahead and Cry.”

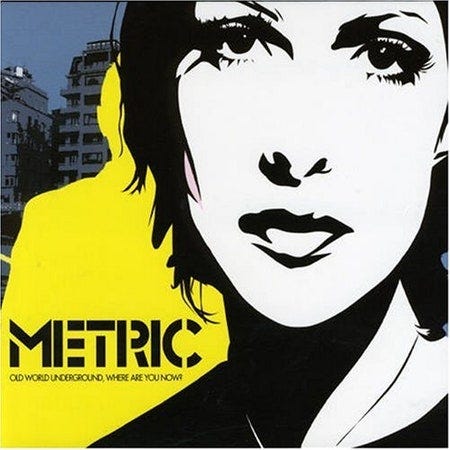

In addition to the release of Formentera II, Metric is also celebrating the 20th anniversary of Old World Underground, Where Are You Now?, their beloved landmark debut album which firmly cemented the Canadian art rockers as a unique and formidable force in the indie rock scene.

To revisit the long road from Old World to Formentera II, I had Haines and Shaw rank Metric’s albums, from their least favorite to most favorite.

8. Grow Up and Blow Away (2007)

This is sort of a complicated one because this was the first album you made, but the third album you released. What are your feelings on it when you listen back to these songs now?

Emily Haines: Pain. Jimmy and I had a five-year journey before we even met up with Josh [Winstead, bassist] and Joules [Scott-Key, drummer], give or take. Leaving Toronto, moving to New York, getting the loft, all these musicians moving in, and then getting this big break to go to England. All the while we’re making our own recordings, we’re working day jobs, Jimmy’s trying to develop as a producer, I’m trying to develop as a songwriter. We’ve got all these songs and we get this total showbiz phone call that was like, “The buzz is too deafening. Just get over here! Don’t even play a show. You’re going to have a Craig David-style record deal.” It was the peak of boy bands and 90s recording artists and it was like we were just getting swept into that reality.

So we leave New York and we go to London and we sign a publishing deal and all this stuff is coming together. We’re going to sign with Food Records because they had Blur. Andy Ross goes into EMI and he’s like, “I got this new band Metric. I want to sign them. It’s this duo, they’re awesome.” And they’re like, “Nope, you’re not signing them and also we’re cutting all your funding.” And this was this moment where the area of London we were living in was also flipping into being gentrified. We showed up when it went from being 70 pounds a week to 350 a week. The same thing was happening in Williamsburg where we had our spot, and we had to come back from getting shot out of a cannon record biz reality and get our jobs back. We were just disillusioned.

But our good luck was that when we came back to New York, what was happening were all these great bands. Interpol and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs are living at our place. TV on the Radio are living at our place. LCD’s studio is just around the corner. The Strokes, the White Stripes, it was just like the perfect climate for us to be like, “Fuck the man, fuck record labels, we’re going to start our own band and just start completely from scratch.” And that meant those songs were getting shelved. And so for me, Old World Underground is the true first album because it’s a manifestation of us starting completely over. And Grow Up and Blow Away is like these fragments of what could have been for Jimmy and I. They’re basically home recordings, sort of like a half caterpillar, half butterfly.

Did you ever think of not releasing it?

Jimmy Shaw: We never had a plan to release it. This guy Chris Taylor started Last Gang Records in order to put Metric out, and he was trying to get a deal for Grow Up and Blow Away really early, and he couldn’t get it done. Then he did and the label went under and blah, blah, blah, all this garbage. So we then made Old World and Live It Out with him, and afterwards, he was like, “My mission is to put out Grow Up and Blow Away.” And we were like, “Uh, weird mission, dude. Like, why? We’re a different band now. We don’t care.” But he just took it upon himself. He thought it was the most important thing. And he did it. He went and got the rights for it and then he put it out. But to me, I had deeply moved on, which is kind of the reason it’s at the bottom slot here.

You mentioned you moved into a loft in Williamsburg right before the boom that happened there. I’m curious if you guys have been back to Williamsburg recently.

EH: Jimmy found this crazy loft on Metropolitan between Bedford and Driggs, and got it by driving the landlord’s dad to the dentist repeatedly. Then he had to take it upon himself to figure out how to get people to move in, because it was like seven rooms or something. One of the first people to move in was Nick Zinner, who would then be in the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and then all these other people.

But I actually did go by there recently by accident because my flight got canceled. I didn’t feel like going all the way back to Manhattan, so I figured I’d just go stay in Williamsburg. And it was so jarring. Luckily, I went to James Murphy’s place, Four Horsemen, because I have friends who got me a spot. So I went there for dinner and did some solo dining and commiserated with the person who was working there about how aggressive it is on Bedford. It’s not like it’s kind of gentrified. It’s like, you lost the war.

I remember when I was living there and the first Verizon store opened on Bedford and it seemed so out of place. And now you walk past there and it’s like Verizon, Apple, Whole Foods, Madewell.

EH: I know! It’s actually helping me that you had the same reaction because I couldn’t tell if I was just sensory overload at the moment.

JS: Where do you live now, Dan?

I’m in LA now, which as you know is completely untouched by this gentrification problem that we’re talking about.

JS: Yeah, corporate America has yet to really sink its teeth into Los Angeles, but it’ll happen!

LA is just never going to go Hollywood, you know?

JS: [Laughs] Yes, totally.

7. Pagans in Vegas (2015)

What do you see as the success and shortcomings of this album?

JS: To me, the success is this: Around 2017, I was perusing through a record bin somewhere and I found this Neil Young record. I can’t remember what it’s called, but all the artwork looks like the security information card on an airplane, like what happens with your flotation device when there’s a crash landing. It’s about an airplane. It’s fully airplane-themed. It was a dollar or something. I brought it home and I listened to it, and it’s the worst fucking piece of shit I’ve ever heard in my life. And what I realized is that you can’t be a legendary artist without massive failures. You have to try and you have to fail.

I think it was at that moment that I had a rekindling of emotion for our record Pagans in Vegas, because I don’t feel like what we attempted to do was a success, artistically. Nothing about commercial success or anything, just on a creative level. I go back and listen to it and I don’t feel like it was a creative success. But I do feel like we were at a very, very difficult time for the band. Everyone was really disparate. We were all over the place. There wasn’t a lot of vibing happening.

What was that attributable to?

JS: Life. We’d been a band for 14 or 15 years at that point, and shit happens. But what I appreciate is that we still went forward. We still tried to do something. We took the best shot at what seemed like the best idea at the time, and we executed it to the best of our abilities. And in my opinion, we kind of failed. And that’s totally legit. And I think that it’s kind of awesome. But that said, I don’t see it as a success.

Emily, what do you think makes a successful Metric album?

EH: The commercial appreciation is one of the things that you consider, but it’s not the only thing. So, in the esoteric way that we go about making art together, the four of us, it’s when there’s just something that happens where, even if nobody else cares, we know that we did it. And I didn’t feel like that really happened on this record, on any of the tracks other than “Cascades,” which has actually become a staple in the live show, which is cool. I love the live version.

But I agree with Jimmy: You’ve got to fail and not sugarcoat it. This album was also quite cursed. Without going into detail of what was going on in my personal life, it was just a very bad time. And then we made the huge mistake of putting out the album and touring it in support of someone else, which is terrible for your fans. You want to do a headline tour when you put out a record. You don’t make them go see someone else. But instead we were opening for someone that people weren’t very happy about us opening for to begin with. And the first day of the tour, Jimmy and I were woken up at five in the morning to be told that our record had leaked. We also found out that our entire crew was stuck at the border because there had been problems with the processing of all their paperwork. And from the airport to the hotel I inexplicably lost my jacket, my sunglasses, and my bag. All my stuff just evaporated. When I look back, it was a bad moment.

The universe’s way of rejecting this album.

EH: One hundred percent. [Laughs]

After this record, you guys worked on a Broken Social Scene record and, Emily, you made a solo record. How do you know when what you’re writing is a fit for Metric or if it’s a fit for another project?

EH: For me, it works the other way around. I just know which direction I should be going by what I’m writing. With Social Scene, it’s more like if I happen to be hanging out with my pals and there’s a window, then it happens. But you will find in lots of our answers to your questions that we have no idea what we’re doing.

6. Live It Out (2015)

I read an interview where you said that a lot of the writing of Live It Out was inspired by the rough experience you had opening for Billy Talent on tour, and that you started thinking of your songs as armor. Can you tell me what you meant by that?

EH: Yeah, it was like… never again.

Never face a hostile audience again?

EH: Yeah, and they weren’t wrong. They were mean. They were beating up Metric fans. It was like high school cafeteria tables, mixing the punks with the art kids. We’re still really good friends with all the guys in that band, actually. But yeah, I mean, I feel like we deserved it. We weren’t good enough yet. Never again will I feel like the audience’s energy is stronger than our energy. And that was really what we experienced, an osmosis problem. So these songs and the tones and the BPMs reflect that.

It feels like more of a punk rock record in spots. Is this the material you pull out when you’re opening for a heavier band?

EH: Yeah. “Monster Hospital” is actually in regular rotation. It’s pretty fun, weirdly. It doesn’t feel that hardcore. But yeah, 100 percent, those songs were to protect us from the audience.

This album and Old World came out right in the middle of that mid-aughts indie rock boom. It’s been long enough that a younger generation is now romanticizing this time and has, for better or worse, dubbed it “indie sleaze.” I’m wondering if you have any thoughts on that term and the romanticizing of that time.

EH: I’m into it. And I hear people being like, “That’s not okay, ‘indie sleaze.’” And I’m like, why? It’s absolutely accurate. Just totally sleazy. Perfect.

JS: I think it’s a girl from Toronto who started that account and kind of coined that term. It’s funny, I was out with some friends last night and I ended up asking a friend of mine, “You love the early aughts, don’t you? You’re so in love with 2005.” She was like, “I am.” And I said, “Would you like to go back to that time at this age?” And she was like, “I’d rather be that age now.” And I was like, “That’s so dumb. I would way rather be this age then. Because there was one really, really, really, really massive difference between then and now, and that’s that everyone didn’t have a fucking phone in their hand, everyone didn’t have a camera, and anything could happen at those shows. You could say anything. And not just from a performance standpoint. Everyone felt that way. There was a point where we used to call it rock and roll church because the common energy in the room could blast off through the ceiling. And the more that people started doing this [holds up a cell phone] and tying it to reality and consequences, the magic left the building, unfortunately.

I was just looking through that book by that photographer, Cobrasnake—

EH: Yeah, Mark the Cobrasnake! He was an early guy in our world. We love Mark. What Mark was doing was like the society photos that you’d see in the New York Times or whatever, at luncheons or galas, but he was doing it at these shows. You totally wanted Mark to be there. And then the next day, you’d look on his website and be like, “No fucking way!”

I was flipping through his book and it was so funny to see what were essentially like A-list celebrities at the time, Ashton Kutcher or Justin Timberlake or Britney Spears or whoever, just hanging out at Williamsburg clubs. And that’s something that was lost too, which is the privacy, whether you’re a celebrity or just some person. I feel like that’s what’s most romanticized now in the smartphone age.

EH: Yeah, I completely agree. I remember the turning point—I was on stage, and by the time I got backstage, someone had sent me a message on my phone about what I was wearing on stage, which now is like, yeah, so what? That’s not even notable now. But that was really unpleasant at the time. That was the beginning of that erosion. It’s not just the deterioration of the experience for the performer where you’re paranoid, it’s about the people in the room. People have a job, they have a life. Your whole existence is now linked to [the internet]. Like, if you lose it at a Metric concert and someone has footage of you losing it at a Metric concert, that’s not good. You don’t want that.

You’ve been a band throughout these two separate eras that we’re talking about. How does it feel now to look out into the audience at a Metric show and see more and more cell phones? Is that distracting?

EH: Nah. I’m of the mindset that we are just lucky that we’ve been able to exist through the coolest time and we’ve gotten the best of so many things. We’ve had to adapt. I remember being sad about it, but I’m over it. What are you gonna do?

JS: I’m not sad about it. It is what it is. That doesn’t mean I don’t 100 percent think it was way better before. It was way more fun for everybody involved. Like, did you ever go to a Vice party in 2005?

Yes, I worked there.

JS: Shit was fun, man. Anything could fucking happen, and a lot of stuff happened.

EH: Yeah, and touring with Test Icicles and Death from Above 1979 across the UK in 2004? It was so fun.

5. Art of Doubt (2018)

Had things gotten a little bit better with the band internally by this record?

JS: For sure. Now you’re kind of getting into the gray zone where all these albums are good and it’s a bit like choosing between your children. But yeah, we were in a good state and we had a really clear vision. We worked with a really talented guy named Justin Meldal-Johnsen. We knew what we were doing. We didn’t take like four years to do it, like we did with Fantasies, and it wasn’t stupid amounts of exploration. It was concise—we’re going to make a rock record, we’re going to get back on track after our weird Neil Young plane crash record, we’re going to remind our fans that we do remember what a guitar is.

Emily, what are your memories of Art of Doubt?

EH: It was just: put on the trench coat and make a rock record. From a style perspective, on Pagans, we worked with this super out there clown guy named John Morris as a sort of stage artist. He had me in all these different get-ups. He had me in this peacock outfit with all this costuming, like a pagan circus gone wrong. So it was really great to just be in black jeans. This was my Iggy With Tits persona, is what I called it. Leather jacket, sparkly metallic bra, black jeans, and boots. It was a really clear moment, and I really enjoyed it. The title track on that album was one of my proudest accomplishments.

4. Fantasies (2009)

I wanted to talk about “Gimme Sympathy,” specifically, because to me, it’s about as perfect as pop songwriting gets. I’m just curious about how that song came together.

JS: It was a really, really hard one to nail the recording of, because it was trying to ride that line of like, it’s a pop song but we’re a rock band, so we were trying to play a pop song as a rock band. One version would land too far on this side, and another version would land too far on that side. It was a really, really tough one to get, but it was such a key sentiment and key song that sort of carried us through the time we’d spent apart and brought us back together.

This is so nerdy, but I keep a playlist of songs that mention other songs in their lyrics. Obviously “Gimme Sympathy” is on there because of the Beatles reference, but I also have Lorde’s “Ribs,” which mentions “Lover’s Spit” by Broken Social Scene. I’m curious if you’ve heard that and if you have any thoughts on being the artist that’s mentioned in a song.

EH: I don’t care one way or the other about it, really. I heard someone has a band called Dead Disco, too. I don’t know. I don’t really care, truthfully.

Wow, really cutting me down on my excitement here.

EH: I’m sorry. Just so you know, it’s not you, it’s me. I don’t care about the things I’m supposed to care about.

I read that after the success of those first two albums, you took some meetings with major labels who were interested in you, but none of them could really sell you on the idea. Why is that?

EH: Well, I can say for me, it’s that the model itself is broken. The exception proves the rule—you’ll always have a breakthrough artist that’s a massive star, being like, “Oh my God, all of it totally worked out!” But the essential premise is: you are given money that [the label] gets to spend—that’s your money—on the people that they choose to spend your money on.

Being packaged would basically take all the powder off the butterfly’s wings for someone like me. I can’t imagine a well packaged, well marketed me. I think that’s a paradox that doesn’t work. I think the authenticity is the entire point of who we are. Even if it was the most ridiculous amount of money, like I said, I don’t care about the things I should care about. To me, the model itself is so busted and broken. And the reason that we’re able to be doing, I think, our best work 20 years in is because we are able to own our own music and own our own existence.

Without naming anyone specifically, it does seem like some of your peers were eager to get that big paycheck because the goal was to cash out. But to me, it always seemed like Metric was a band whose goal was to keep going indefinitely, and that is the reward.

JS: That’s 100 percent accurate. That was something I think we knew from the very beginning. We were saying this on our last tour—it seems like it’s way more commonplace in the UK to be in a band when you’re 20 to 26, blow up, have a bunch of success, date a celebrity, have a drug habit, do the thing, be in the NME, puke in the alley, blah, blah, blah, and then you pull your shit together. Like, “I never intended to do this when I grew up. This is just something you do when you’re young, you know?” And fair enough, that’s awesome. I’m kind of glad that a lot of those bands didn’t do it until they were 50 years old. It would have been awkward. But for us, the point was always to do this for as long as humanly possible. And we’re halfway there. [Laughs]

3. Synthetica (2012)

This was the first album that came out after you had a hit song in the movie Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World. Did you notice that having any effect on your fanbase? Did you get a lot of new fans from that?

EH: It’s weird, it’s sort of more now. This is an example of us just being a little bit out to lunch. I remember we were always like, “Oh, yeah, that movie, cool.” I don’t know, it just didn’t register or something. Like, Nigel Godrich, Michael Cera, cool. I remember playing Comic-Con and we were backstage with all those guys, and we were like, “Yeah, right on. This is awesome. Anyways, see you later, guys!” [Laughs]

JS: Nothing’s ever happened to us where all of a sudden you show up and our crowd is double the size. It’s never happened to us. No matter what it was—[Scott Pilgrim], Twilight, all the stuff that’s happened. Metric’s career path has been a straight line. Every single time we play in a city anywhere, it goes up by like four percent every single show for 20 years. I don’t know why it’s like that.

But it’s a good way to avoid being a one-hit wonder.

JS: Yeah, and we kept sort of expecting that one of those things would happen. Like, Twilight was kind of the biggest one. It was the biggest movie franchise ever at that point. And we did the theme song, we went to the opening gala thing, and did the red carpet, and Pattinson’s there, and all the stuff. And then you book a tour and… there’s your fans again. Nothing ever blew us up. And yes, I think you’re right. In the long term, it’s probably why we’re still here.

This album, like a few of your albums, won a number of Juno Awards. Do you care about awards and that kind of stuff?

EH: I think it’s all sort of the same thing. It’s this inertia, this positive momentum that all keeps the little train chugging along the tracks. It’s helped us not ever slide backward.

2. Formentera (2021)

Forgive me for doing the most cliché thing and asking how the pandemic affected your songwriting, but sonically and thematically this does seem like the darkest Metric record. And I’m wondering, well, how did the pandemic affect your songwriting?

EH: Thank you! [Laughs] Yeah, the whole approach we took was to make an escape. That explains the name, obviously. I leaned pretty hard on Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, a wink for any cinephile people who saw that reference in the font and everything. For those of us who did not quarantine on a yacht, the pandemic was really hard. Obviously, musicians were affected deeply, profoundly, as was everyone. For me, it was the idea of the loss of control, the illusion of control that we all had over our lives that was very quickly exposed as soon as there was a crisis.

So we made these big moves—we’re going to buy a church, we’re going to build a studio, we’re going to make this place itself an escape. And the music that we’re making here is an escape for people who can’t physically go anywhere. I think you hear that in the album, that we tried to just make something as beautiful and helpful as possible.

Was the plan to make a two-part album originally?

JS: We didn’t have a plan. This was June 2020. No one had a plan. The plan was just to get to the other side. We started making music in the summer of 2020 in a rural, remote location because we were part of planet Earth at the time, which was a trip.

When there was a planet Earth still, yes.

JS: When there was a planet Earth, yeah. When there was one cohesive idea that was planet Earth, before you could just argue anybody’s point of view. So we were making music up there and we just kind of kept going and going and going and going. And I think that if it had been under normal constraints, we would have finished a record and we would have put it out. We would have probably toured a year and a half earlier than we did. But nothing was returning. We just kept going, and we were on such a musical creative tear that we made way too much music for one record. As it was happening, we started realizing: OK, we’re not going to stop and put this music out right now because the timing is not correct, and we’re going to have more than a record’s worth of material. So let’s just keep going. Let’s make sure that we have two records’ worth of material. We’ll put one out and suss the situation from there.

1. Old World Underground, Where Are You Now? (2003)

What about this record earns the top slot?

JS: It’s really deeply in our consciousness right now because it’s the anniversary. We just came off a rehearsal where we were playing a bunch of these songs again. If we did this interview three years ago, I probably would have wrongly put it like eighth or something, you know? But the aesthetic of what we were doing then was so clear. We’ve had 20 years to exist now. We’ve grown up, we’ve aged, we’ve become broader people.

EH: Yeah, you own more than one pair of pants now.

JS: Yeah, exactly. We had one pair of pants then and we were all wearing them on stage. But looking back, it was such a clear vision, and if it wasn’t that clear when it started, I don’t know that it would have worked, you know? And our whole life is based on it at this point.

I used to have a sign in my old apartment that said, “I’m sick, you’re tired, let’s dance.” I’m sure you’ve seen your lyrics tattooed on people and things like that. Are there any surreal instances of seeing your lyrics out in the world?

EH: Yeah, tons. Anytime it’s a tattoo, that’s very deep to me. But on the topic of caring about things, that I do care about, that you had that on your wall. I’m really honored by that. That’s like an award.

Emily, you lost your father the day you finished making this album. Your dad was a poet. What do you think he would have made of seeing his daughter have this big, long success as a songwriter?

EH: Oh, I mean, he was such a supporter and was so much of the reason why I was doing what I was doing. Jimmy was really close with my dad, too. He’d be so happy. But it does add a layer to this time. It’s hard to put in words.

Does preparing for the anniversary of this record stir up any of those painful memories for you? Or can you detach and just play the songs?

EH: It’s very stirred up because it set off a sequence of events. I kind of blew up my life, or my life blew up. We were trying to get stuff going with the band, and then this record came out, and the Broken Social Scene album came out, and we were in that Olivier Assayas film, Clean, and I made my album, Knives Don’t Have Your Back. All the things and all the grief. All this stuff just happened at once. I kind of feel like I was never the same again from that moment.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Additional reading:

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Man Man

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Dillinger Four

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Touché Amoré

ᐅ Rank Your Records: The Menzingers

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Planes Mistaken for Stars

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Rise Against

ᐅ Rank Your Records: Death Cab for Cutie

Follow me on the internet. Instagram | Threads | Twitter | Website

Get my book SELLOUT at Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

Love these pieces, but especially ones like this where the band is very thoughtful about their answers and yet you look at where one of the albums is ranked (in this case, Live It Out) and if it were anyone but the band I'd click away as obvious ragebait (see also: Titus Andronicus)

I love these Rank Your Records pieces, they are so well done and I could read one every day.